It’s hard to decide which game to play today! gameaudio gamesofgameaudio

Oh Joy! This recording finally sees the light. Very limited amount of copies. Pre-order now. See the movie soon.

![12 Picture Disc [GD30PD]](http://scottcolburn.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/MT502_sideA_preview_original-300x300.jpg)

A Personal Favorite

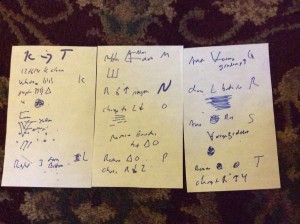

#drinksofgameaudio #musicofgameaudio #EsotericaofAbyssynia

Name check in this article! Probably some of my best work.

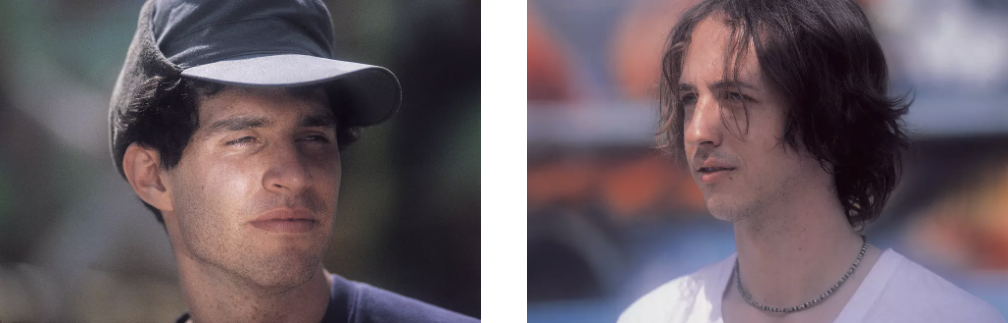

Photographer CEDRIC BUCHET

September 16, 2015

In 2005, writer Charles Homans hung out with Animal Collective for this story from The FADER’s 33rd issue, which also happens to be the Brooklyn-via-Baltimore band’s first ever cover.

So, let’s say that you were a little kid once—most people were—and let’s say that your littlekidhood was followed by a drug-and art-damaged adolescence, which was followed by the beginning and premature end of a college career, and then a string of dull day jobs that at some point became adulthood. And let’s say that somehow through it all, you maintained a focus on—even a near-obsession with—those years you spent screwing around in the city parks and suburban woodlots that pass convincingly for endless forest when you’re less than four feet tall, pretending that you were all sorts of things you hadn’t yet learned didn’t really exist in the late 20th Century: a pirate, a knight, a cowboy. By this time, you’ve replaced your given name (Dave Portner) with a mildly absurd variation on it (Avey Tare) and you’re playing guitar and singing in a band (Animal Collective) with people who share your obsessions—some of them actually knew each other when they were less than four feet tall and one of them calls himself Panda Bear. You start cranking out records with the speed and aesthetic sensibilities of a hyperactive six year-old with a box of crayons. They have hand-scrawled artwork and song titles “Who Could Win a Rabbit” and “Doggy.”

This leads, paradoxically, to a lot of not-very-childlike situations, like a show in a converted church in Minneapolis where some of your fans eat an acid-laced pizza and try to take your socks off while you’re playing. But you sense there’s some sort of payoff coming, one your sub-four-feet self would recognize, and one day the phone rings. A guy says he has a pirate ship in France that he’d like you to play on. Bingo. But early in the evening of August tenth, Portner, the other three Animal Collective members and their sparse entourage—a girlfriend, a sound tech and a French filmmaker with a Super 8—seem too exhausted and irritable to really grasp the appropriateness of the show they’ll play in a few hours at La Guinguette Pirate, a Parisian club housed in a replica of a Chinese junk called La Dame du Canton and anchored below the Bibliothèque François Mitterrand on the Seine. Because it turns out that pirate ships present a lot of technical difficulties you don’t think about when you’re seven. The boat rocks in the wake of the barges that navigate the river at regular intervals, knocking Portner off balance during soundcheck. And it’s a French pirate ship, which is a problem both because nobody in the band speaks much French and because there’s a 110-volt gap between the American and European electrical systems, causing La Guiguette Pirate’s fuses to blow with a loud pop every time Portner tries to plug in the tools of Animal Collective’s blurry psychedelia—amps, chains of effects processors, a sampler, a row of minidisc players, a homemade circuit blender. The sunlight that spills across the Seine in the early evening makes for nice photographs and paintings, but it also makes the inside of La Guinguette Pirate feel like an unventilated attic in August. And when the band tries to work out a setlist before the show in the cramped upper compartment of a nearby double-decker bus that has been transformed into La Guinguette Pirate’s crepe stand, a cook angrily stomps up the steps to tell them not to move around. They’re shaking the bus and ruining his crepes, he says.

“I think we have a strange relationship with words.”—Noah Lennox, aka Animal Collective’s Panda Bear

Animal Collective is on the front end of a rushed three-day, two-show stint in France, to which they’ve all parachuted from different places. For the first extended period of time since they started playing music together as high school kids in Baltimore, the band’s four members—Portner, Panda Bear (Noah Lennox on his tax returns), Deakin (Josh Dibb) and Geologist (Brian Weltz)—aren’t within driving distance of each other. Porter has set himself up temporarily in Paris, and in the past year Lennox moved to Lisbon with his wife, a Portuguese fashion designer, and had a kid. Weitz is in Washington, DC now, doing environmental work, and only Dibb is still hanging around the band’s former base of operations in Brooklyn. It’s alien territory for a band used to a close-knit existence and a heavy touring schedule, and they’re wandering around in it, unpracticed and jet-lagged.

But in a few hours, when the sun goes down, things will look up. The boat will fill with people—mostly male record-collector types in their late 20s and early 30s—who hang off the mast and sail-less boom of La Dame du Canton like overgrown Lost Boys. Once the show is in full swing, they’ll be happy to join Animal Collective in its goofy pseudo-tribal dances, the sort of thing most bands have been too cool for since Pearl Jam’s Vs tour. And they won’t seem to mind when the band plays just one song off of Sung Tongs, its critical breakthrough from June 2004 and probably the reason why most of the crowd is here. Instead, they’ll climb on benches and windowsills and do whatever is required in La Guinguette Pirate’s shoebox-like interior to get a glimpse of the floor-level stage, as if Portner is holding some sort of tiny secret in his hands and the show will be a waste of their time and money if they don’t see it.

“There’s a pop song in every one of those tracks—it’s just embedded and surrounded by this blanket of fucked-up sounds.”—Scott Colburn, Feels’ producer

The songs that the Lost Boys hear onboard La Guinguette Pirate—most of which will appear on the new Animal Collective record, Feels—have lived like this for more than a year: on the road, in loud and sweaty incarnations that stretch their limbs when they feel like it, sometimes with inspiration and sometimes with indulgence. Describing the band and its music without giving people the wrong idea is hard, and the members of Animal Collective don’t really help their case when they use the word “jamming” without irony and say the original Grateful Dead lineup is the only band they would open for on tour (they’ve turned down offers from bands that a lot of musicians in their scene would consider more enticing).

The songs sound more subdued and disciplined on Feels, which is a different kind of Animal Collective record. Past entries in the band’s catalog—which now stretches to seven albums and at least that many singles, split 12-inches and compilation appearances—have been relatively informal projects with sometimes as few as one Animal present, varying production values and a general contempt for brand identity. (The band explains via email that it formally adopted the Animal Collective monkey in 2003 for Here Comes The Indian, the only studio full-length besides Feels with all four Animals on board, only because “to have all four names on a cover or a poster was not very attractive. Record labels also started to mention that the band needed one name so that people could recognize them.”)

For Feels, Animal Collective sought out a specific producer for the first time and hired Scott Colburn, mainly because of his work with noise legends the Sun City Girls. The band slept, ate and watched horror movies in Coburn’s Seattle studio—another converted church—for a month. They did eight or nine takes of songs and sprawled across a hundred-plus tracks of overdubs. They did the sorts of things you’re supposed to do when you make a Rock Masterpiece—and came away with a record that kind of is one. On Sung Tongs, Animal Collective wore its encyclopedic knowledge of its influences—’60s hippie outsiders, high concept avant-gardists and its predecessors in the early ‘90s indie rock scene—on its sleeve. On Feels, they swallow those influences whole. “There’s a pop song in every one of those tracks—it’s just embedded and surrounded by this blanket of fucked-up sounds,” Colburn says, and he’s right, although sometimes you have to take him on faith.

“It’s almost like I don’t want people to know exactly what I’m saying.”—Dave Portner, aka Animal Collective’s Avey Tare

Instruments run together like a child’s watercolor set, lyrics disappear into meticulously dense arrangements, and at times the songs are delivered with such a soft touch that they seem to be in danger of evaporating before they run out their time. The whole thing sounds like a trick of the light. You also have to assume that Portner is telling the truth when he says things like, “Ink is a major theme in our music.” Two days after the Guinguette Pirate show, he’s covering his face in streaks of the stuff, blue and purple ink, in Animal Collective’s dressing room in a dreary ‘70s-vintage convention center in Saint-Malo, an otherwise medieval-looking city of about 53,000 on the Brittany coast, where the band has landed a choice gig on the second stage at the La Route du Rock festival. The room is deserted except for Kristín Anna Valtysdóttir, the Icelandic pianist who plays in Múm and Mice Parade and on Feels, who is alternately doing handstands, reading a guide to the Kabbalah, and trying to figure out how to fly her kite indoors. The other Animal Collective members drift in and out. As the ink dries, Portner explains, “You use ink to write letters. Ink brings people together. I like the idea of different colors of ink, running together.”

You also use ink to write lyrics that are so private that you smear them in all kinds of figurative ways so people can’t figure them out. You bury them in lush Beach Boys harmonies or under landslides of guitar atmospherics, or you stir them together with fragments of literalism and armchair mysticism until it’s hard to tell which is which. If Animal Collective’s eight year-deep songbook came with an index (and it probably should), a random pair of adjacent entries would read something like:

Danse Manatee (Catsup Plate, 2001; reissued Fat Cat 2003). See also “Manatees, mating habits of, as seen on nature special viewed by Panda Bear.”

Death of father. See “Panda Bear: Young Prayer (Paw Tracks 2004), inspiration for.”

“I think we have a strange relationship with words,” says Lennox, who with Portner constitutes half of Animal Collective’s songwriting core (they’re the only two members on Sung Tongs). “What we’re writing about is extremely personal—maybe so personal that we don’t want the lyrics too high in the mix. It’s almost like I don’t want people to know exactly what I’m saying.” Portner falls silent for a second, then grimaces. He scratches at the dried blue and purple lines running down his cheeks. “Man, it really burns.”